Understanding PBM Compensation – Part III

This three-part series examines the business practices of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and identifies potential policy solutions to address misaligned incentives in the pharmaceutical supply chain.

Untangle Complexity

11/01/2021

Read time: 6 min

As reviewed in Parts I & II of the PBM Transparency series, PBMs are used by health insurers or plan sponsors to manage prescription drug expenditures. Predominantly, PBMs manage drug costs through the supply chain (upstream) and through demand (downstream). Upstream, PBMs negotiate rebates with pharmaceutical manufacturers and discounts with retail pharmacies to lower the net drug cost. Downstream, PBMs implement a variety of mechanisms for plan participants, or patients, to limit or redirect drug utilization. Patients taking medicines often don’t directly benefit from the upstream drug cost management because their access and cost-sharing do not always factor in the extracted rebates and discounts. Moreover, patient access may be negatively impacted by the downstream mechanisms through the restriction of drug utilization by therapy delays, coverage denials, and complex policy guidelines.

PBM Management of Demand: Coverage

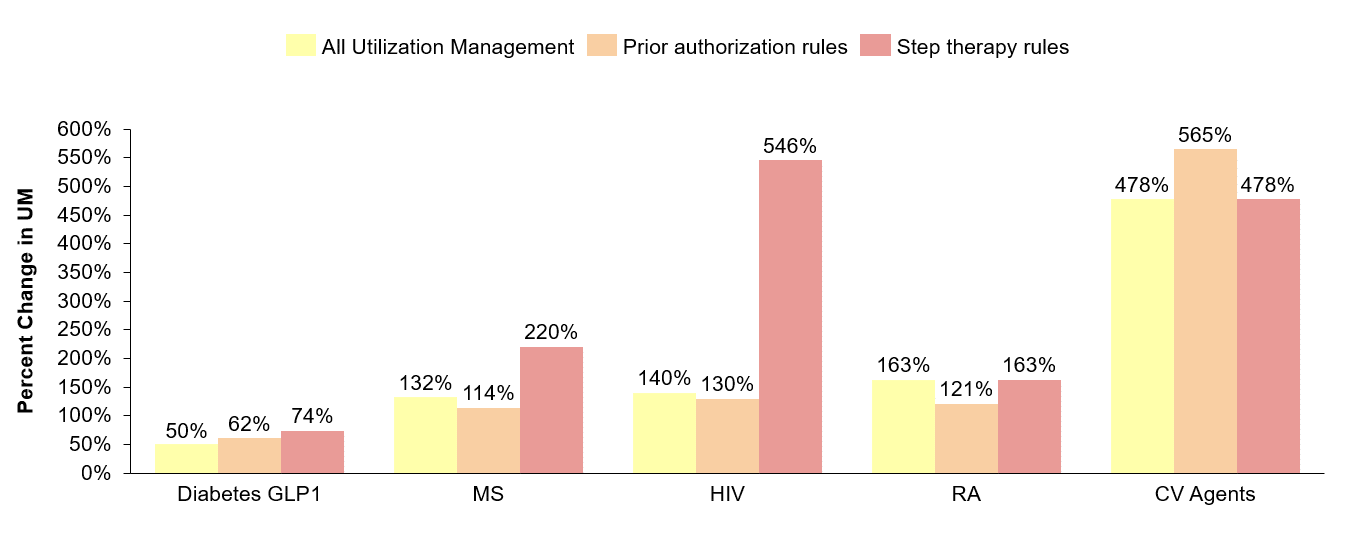

PBMs seek to restrict or guide demand through the implementation of utilization management tools which are typically linked to the design of drug formularies. The utilization management mechanisms PBMs employ include exclusions, prior authorization requirements, and mandated treatment pathways that require “steps” or trials through other drugs. These decisions have direct consequences for health care providers’ ability to prescribe medicines and patients’ ability to access medicines.(1) According to research conducted by Avalere Health in 2021, commercial plans’ use of major forms of utilization management restrictions increased between 2014 and 2020.(2) Moreover, since 2019 the two largest PBMs have substantially increased the number of excluded products – growing 96% at CVS Health (from 179 to 333 drugs) and 51% at Express Scripts (from 242 to 366 drugs). Additionally, they have exerted more control among typically hands-off classes, including oncology in 2017 and HIV in 2019.

Historically, most utilization management decisions were enacted annually (at the start of each plan year), which, while disruptive, at least offered some predictability for patients. However, PBMs are increasingly implementing mid-year formulary changes or exclusions that could disrupt a patient’s continuity of care. While prior authorizations and other utilization management restrictions can often be used to ensure appropriate use of medicines, the increasing frequency with which these management tools are implemented could make it harder for patients to access medicines they need.

PBM Management of Demand: Cost

In addition to utilization management tools that restrict coverage, PBMs also leverage a variety of cost-sharing structures to influence a patient’s use of medicines. Deductibles and co-insurance are two ways that insurers typically benchmark patients’ cost-sharing to the list price of medicines, which does not account for rebates and other negotiated discounts received by the insurers. These cost mechanisms are increasingly common – today, half of all patient out-of-pocket spending on brand medicines is attributed to deductibles and coinsurance.(3) Many brand products have large rebates and discounts that significantly lower the cost of medicines. For example, the Senate Finance Committee (SFC) released a report in 2021 noting that PBMs have negotiated rebates in excess of 70% for insulin products.(4) However, these savings are generally not passed through to patients with diabetes. Consider a patient with a $500 deductible attempting to purchase insulin, with a list price of nearly $300 per vial. The negotiated discount as reported by the SFC should enable the patient to pay no more than $85 – instead, because the patient has not yet met their deductible, the patient will pay the full undiscounted price ($300) and the payer will pocket the $215 rebate.

By excluding products with lower list price and linking patient costs to list price instead of net price, patients are paying more than they should for their prescription drugs.

Beyond deductibles and coinsurance, many plans also design formularies with multiple tiers, which correspond to different cost-sharing thresholds. On higher tiers, patients face higher out-of-pocket expenses; typically, medicines are placed on higher cost-sharing tiers to encourage patients to use a lower-cost alternative. However, the decision-making behind formulary design is not transparent, and patients have a limited ability to advocate for personalized care or exceptions. Formulary design can also negatively impact patient access, as evidenced by PBM decisions to exclude lower cost hepatitis C treatments and insulin products in favor of medicines with higher list prices.(5)

Potential Policy Solutions

There are several policy solutions that could address increasing patient out-of-pocket costs and re-direct PBMs’ cost reduction aims to the appropriate beneficiary – the patient. It should be noted that many states have already begun to take action against PBMs, including West Virginia, which passed a law requiring PBMs to share rebates provided by manufacturers directly with patients at the pharmacy.(6) Ohio’s attorney general also filed suit against the PBM Centene for misrepresenting pharmacy costs and fraudulent overpayments from the state’s Medicaid program, which resulted in an $88.3 million dollar settlement.(7) States have, and will likely continue, to take actions, but federal actions could supersede and ensure consistency and common expectations for everyone. Those actions should include:

- Formulary Review Transparency: A more robust formulary review process should be enacted to ensure formulary decisions reflect the best interests of patients. To that end, protections should be strengthened to ensure patients have consistent, uninterrupted access to medicines. Negative mid-year formulary changes should be prevented, and patients with established treatment regimens should be continuously covered.

- Ban Accumulator Adjustment Programs (AAPs): Today, many PBMs and commercial health plans use AAPs to exclude cost-sharing assistance from patient cost-sharing requirements, including deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums. However, many patient advocates argue that these programs result in higher out-of-pocket costs for medicines.(8) Currently, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, Connecticut, and North Carolina have all passed accumulator adjustment program (AAP) bans.(9)

- Close the Essential Health Benefit Loophole: Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), insurers are required to provide a set of essential health benefits (EHB), which are subject to an annual maximum out-of-pocket limit for patients. Once this maximum threshold is hit, a patient’s insurance covers the remainder of costs for the year. However, some health plans are able to deem certain items and services – including some prescription drugs – not to be EHBs. Since non-EHB items and services are not required to be subject to an annual out-of-pocket limit, patient cost sharing for those benefits can have no limit (so their insurance might never “kick in”).(10) This undermines measures designed to protect affordability for patients. Policy solutions should ensure that all covered items and services are considered essential health benefits.