The Inflation Reduction Act – Part II

Part II in a series covering the Medicare drug pricing reforms enacted by the Inflation Reduction Act

Untangle Complexity

10/10/2022

Read time: 12 min

Background & Context

On August 16th, 2022, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) into law, with a primary goal of lowering prescription drug costs in Medicare. The IRA seeks to achieve this goal through three main provisions: government negotiation of Medicare drug prices,(1) penalties on Part B and Part D medicines with prices growing faster than inflation, and a redesign of the Part D benefit. With this series HCG is focused on the implementation of the drug negotiation program (DNP) in 2026. In part I, we reviewed several unknowns surrounding implementation and which therapeutic areas & manufacturers are likely to be impacted first. Through this paper, and the remainder of the series, we unpack the anticipated impact of government negotiation on payer contracting and competitive dynamics in Medicare Part D using the following scenarios of interest:

- Therapeutic Area with One Government Negotiated Brand (today’s focus)

- Therapeutic Area with Two Government Negotiated Brands

- Therapeutic Area with a Government Negotiated Brand in Medicare Part B

Across these scenarios, HCG will evaluate how brand medicines subject to drug price negotiation (hereafter referred to as DNP brands) and non-DNP brands will seek to compete in the Part D market and the resulting implications for plans and manufacturers. We will review how this process could unfold, highlighting various stakeholder incentives and potential market dynamics.

Scenario #1 – Therapeutic Area with One Government Negotiated Brand

For the first scenario, HCG will discuss an illustrative protected Part D class with three brand drugs, one of which is a DNP brand. HCG assumes the following market dynamics:

- List Price: All three drugs have a monthly WAC above the Medicare specialty threshold tier, ranging from $13,500 to $15,000 per month.

- Competition: Today, the market is dominated by the DNP brand, Drug 1, with an 80% market share in Medicare. Since this is a protected class with required coverage of all medicines, HCG assumes current payer rebates for all three brands are low, at 15% of WAC.

- Differentiation: While all three drugs have similar efficacy, Drug 2 (which is not subject to government negotiation) has a slightly better safety profile.

- Maximum Fair Price: Drug 1 qualifies as a short monopoly drug, meaning that the ceiling for government negotiation is at most 75% of the non-federal average manufacturer price (non-FAMP).(2) As mentioned in part I, HCG assumes that the non-FAMP is 80% of WAC.(3,4) While the law allows HHS to offer a negotiated price below this ceiling price for modelling purposes, HCG assumes the maximum fair price (MFP) for Drug 1 is equal to the ceiling price, which is a 40% discount from WAC.

Interaction of Government Price Negotiation and Part D Redesign

To understand the impact of government price negotiation on Part D market dynamics, it is important to highlight how it interacts with the Part D redesign component of the IRA. New competitive dynamics introduced by the Part D redesign are likely to affect stakeholders’ formulary and contracting decisions for DNP and non-DNP brands:

- Plan Liability: Part D redesign will substantially increase plan liability for high-cost medicines. This is a significant change from the current benefit design, where high-cost medicines are heavily reinsured by CMS in the catastrophic phase of coverage.

- Manufacturer Liability: Part D redesign adds new manufacturer liabilities in the initial coverage and catastrophic phases. For DNP brands, manufacturers are not subject to these liabilities, which are covered instead by CMS.

- Cost Benchmarks: Stakeholder liability and patient out-of-pocket costs are based on different cost benchmarks for DNP and non-DNP brands. For DNP brands like Drug 1, the cost benchmark is the MFP. For non-DNP brands like Drugs 2 and 3, the cost benchmark is a retail price close to WAC. In many instances, plan liability is likely to be significantly lower for DNP vs. non-DNP brands.

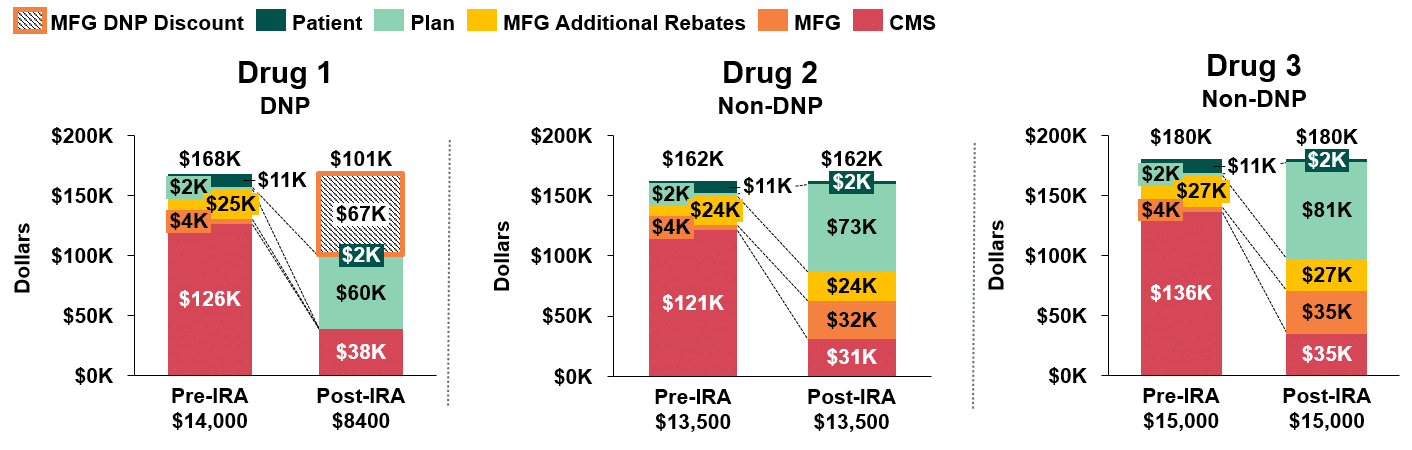

In Figure 1, we compare annual stakeholder liability pre-and post-IRA implementation for the three drugs in our first scenario. We assume that discretionary rebates to the plan remain the same for the two non-DNP drugs and that the manufacturer of the DNP drug does not offer any discretionary rebates post-implementation.(5)

The first key takeaway is the significant increase in annual net plan liability for all three drugs (ranging from $58k-$79k per patient), attributable to the Part D redesign. The second is that net plan costs for the DNP brand, Drug 1 ($60k), are significantly lower than for the non-DNP brands, Drugs 2 and 3 ($73k and $81k, respectively).

Figure 1: Stakeholder Liability Comparison Pre- and Post-IRA Implementation(6)

Plan Considerations

As plans head into post-IRA contracting cycles, they will likely seek to offset their increased liability and mitigate risk by adding utilization management restrictions or seeking higher manufacturer rebates for non-DNP brands.(7) Plans can also offset a portion of their increased liability by increasing premiums. However, given the importance Part D enrollees place on premiums when selecting plans, HCG does not expect that plans will turn to premium increases to absorb all of their increased liability. With this in mind, HCG expects plans will pursue one, or both, of the following strategies as they establish their formularies:

- Seek to limit liability & risk through formulary exclusion or utilization management restrictions for non-DNP brands:

- Since this scenario considers a Part D protected class, plans do not have the option to exclude Drug 2 or Drug 3 from the formulary, as they are required to provide coverage for all drugs in the class. Outside of the protected classes, plans are only required to provide formulary access to two drugs per class, and thus plans could exclude Drug 2 or Drug 3 from the formulary and apply utilization management to restrict access to the remaining non-DNP brand.

- Increase utilization management restrictions for Drug 2 and Drug 3 in an attempt to reduce their market share. This strategy grants preferential access to the DNP product, Drug 1, while providing limited access to the non-DNP brands.

- Seek to reduce liability & risk through higher rebating:

- Reduce plan liability for Drug 2 or Drug 3 by pursuing higher manufacturer rebates. To maximize rebates, plans may offer better access (e.g., a lower cost sharing tier, less stringent utilization management) to the non-DNP drug that provides the lowest net cost.

- Seek higher rebates across all competitors, thereby attempting to balance open access for all products while reducing the plans’ liability across the three brands. This would help to reduce plan liability for Drug 1, which despite being subject to negotiation and lower net costs overall, still leaves plans with a significantly higher liability than prior to the IRA.

In the absence of securing higher rebates for non-DNP brands, plans will be incentivized to limit access to these products by directing patients (via non-medical switching policies, cost-sharing differentials, etc.) to the DNP brand, Drug 1. However, in seeking to reduce utilization of non-DNP brands, plans may face the following challenges:

- CMS Regulations – As noted above, Part D regulations require plans to cover at least two products per USP class and all or substantially all products in the six protected classes.

- Current Market Share – If a non-DNP brand has substantial market share, it may be more challenging for payers to successfully switch all patients to the DNP brand.

- Clinical Differentiation – Payers may face challenges switching patients in therapeutic areas where individual patients respond best to different treatments.

- Prescriber Preferences & Capabilities – For many specialty classes, prescribers may be familiar with and willing to fight through medical exception policies to secure non-preferred therapies for their patients.

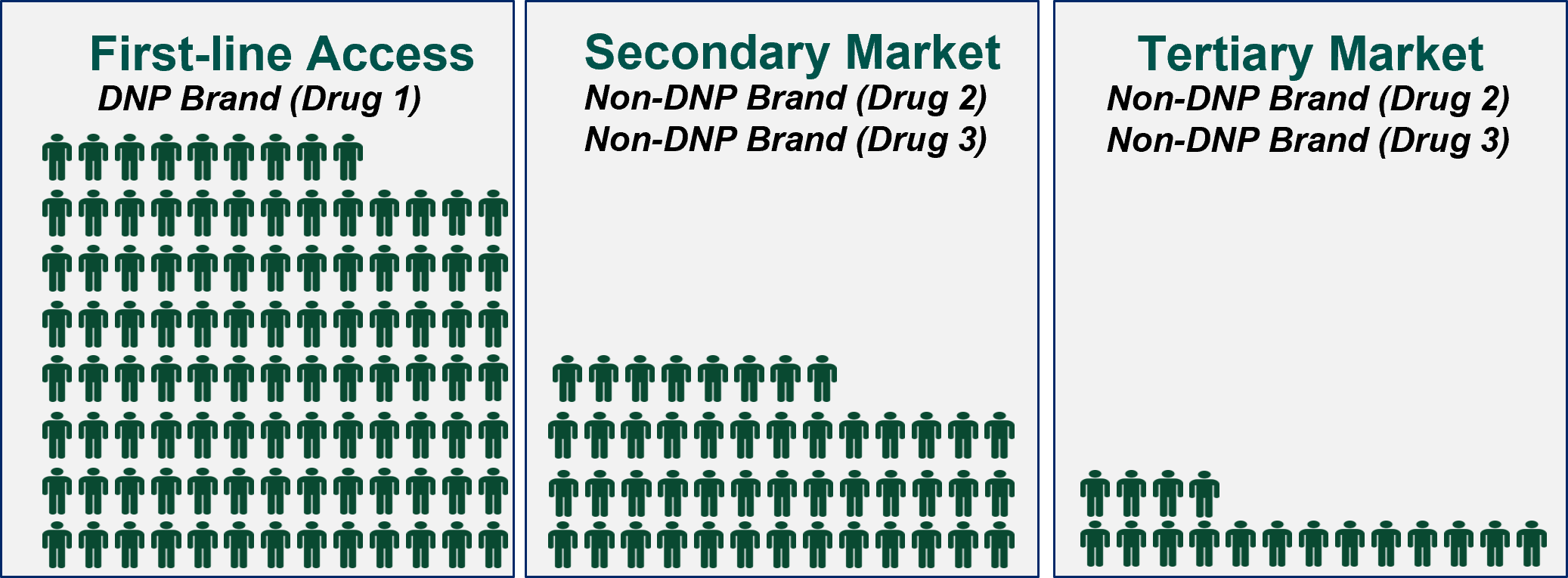

Ultimately, HCG believes that the degree to which plans can steer utilization within a therapeutic class is directly related to the market’s demand, or clinical need, for multiple treatment options. Clinical differentiation creates the opportunity for non-DNP brands, like Drug 2 and Drug 3, to compete for a secondary or tertiary share of the market, even though it may only be a sliver of the market they compete for today.

Figure 2: Illustrative Market Size for DNP and Non-DNP Brands

In a post-IRA world, we expect that plans will be incentivized to restrict access to non-DNP brands via utilization management restrictions or formulary exclusions, as appropriate, or by seeking higher rebates in exchange for preferred treatment of these products. The extent to which plans are successful will depend on the response from manufacturers and the market.

Manufacturer Considerations

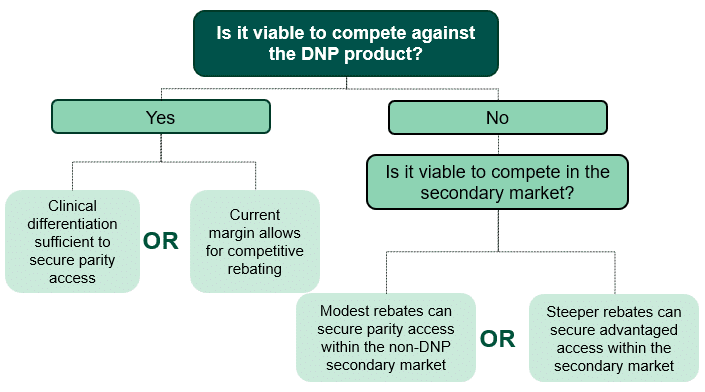

In our first scenario, the manufacturers of the two non-DNP drugs (Drugs 2 and 3) must decide if they will seek to compete against the DNP brand (Drug 1) or if they will only look to compete within the secondary market. For Drug 2 and Drug 3 to effectively compete against Drug 1, HCG assumes that one of the following would need to be true (outlined in the decision-tree in Figure 3):

- Drug 2 or Drug 3 has sufficient clinical differentiation to secure advantaged or parity access to Drug 1 with limited or no incremental discretionary rebating.

- Drug 2 or Drug 3 has enough margin to offer sufficient incremental discretionary rebates to plans, such that their net price is competitive with that of Drug 1.

If it is not viable for non-DNP brands to compete with the DNP brand, manufacturers may decide to limit competition for volume to the secondary market. Robust competition within the secondary market may be more likely in cases where Part D regulations, current market share, clinical differentiation, or physician preferences make it difficult for plans to severely restrict access or eliminate coverage of non-preferred therapies. For our first scenario with required coverage for protected class therapies, competition within the secondary market could include Drug 2 or Drug 3 providing modest rebates to secure parity access with one another. Alternatively, Drug 2 or Drug 3 could provide larger rebates to secure advantaged access within the secondary market.

Figure 3: Decision Tree for Non-DNP Manufacturers (Drugs 2 and 3)

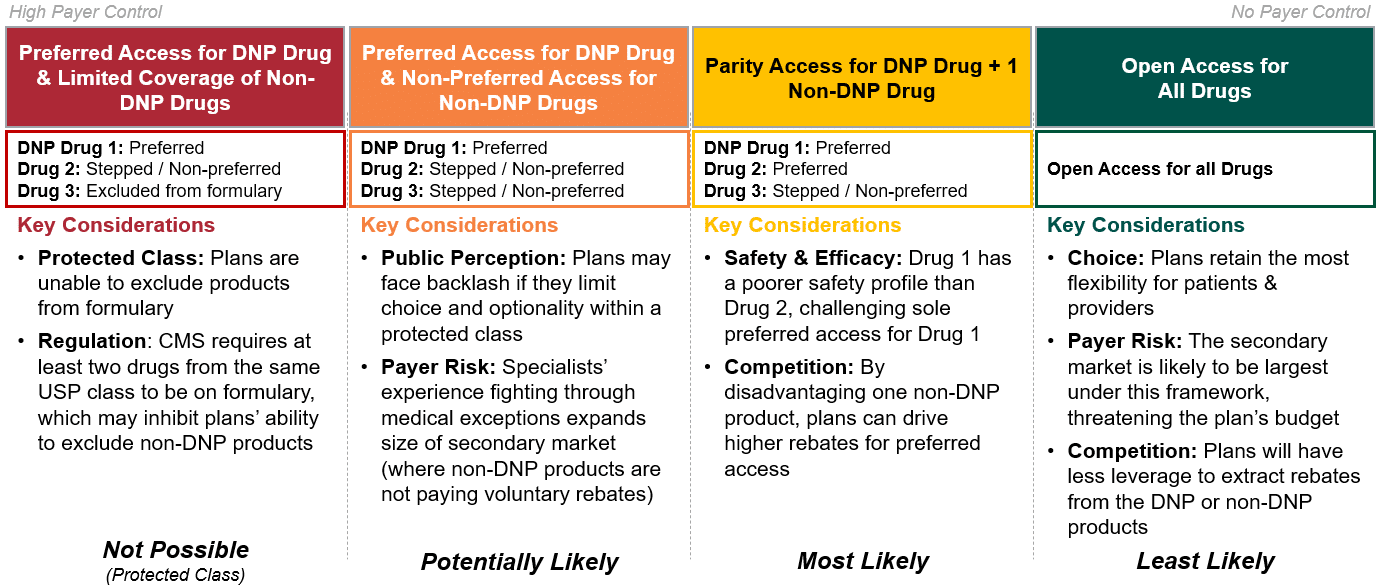

Scenario 1: Market Outcomes

In Figure 4, HCG has outlined the set of market outcomes for our first scenario. Given the market dynamics at play for scenario 1, HCG expects it is most likely that plans will prefer the DNP drug, Drug 1, and offer parity access to either Drug 2 or Drug 3 in exchange for higher manufacturer rebates. Because this is a protected class, plans cannot exclude Drug 2 or Drug 3 from coverage; however, plans may designate these products as non-preferred and limit access via prior authorization and step edits.

Figure 4: Strategic Option Set for Medicare Part D Plans

Key Takeaways & Next Steps

Competitive dynamics in Medicare Part D will look vastly different post-IRA implementation. As scenario 1 begins to show, the degree of market disruption will vary based on several factors including Part D coverage requirements, clinical differentiation, and plans’ willingness and ability to restrict access to non-preferred therapies. While there are many unknowns, breaking down expected market dynamics for our first scenario of interest has highlighted the following anticipated outcomes:

- Plan Liability: Plans will take on increased liability as a result of Part D redesign, particularly for high-cost medicines. To limit liability and mitigate risk, plans are likely to impose utilization management restrictions to limit market share for non-DNP drugs and/or demand higher rebates for formulary access.

- Manufacturer Revenues: Government price negotiation will reduce manufacturer revenues not just for the DNP brand, but for all products in the therapeutic class. Manufacturers of non-DNP brands are likely to see substantially lower revenues due to plans’ increased use of utilization management to limit market share and/or demands for higher rebates.

- DNP Brands: For many higher-cost medicines, plan liability will be substantially lower for DNP-brands vs. non-DNP brands. However, plan liability for DNP-brands is likely to still be higher than under the pre-IRA Part D benefit. Discretionary rebates for DNP brands are likely to be limited, as manufacturers will have minimal margin to provide incremental discounts to payers.

- Non-DNP Brands: Plans are likely to seek higher rebates from non-DNP brands in exchange for formulary access. At a minimum, non-DNP brands will need to provide rebates to gain access, or favorable access, to the secondary market. Outside of the protected classes, non-DNP brands may need to provide steep discounts to avoid formulary exclusion. Importantly, these dynamics are likely to begin prior to implementation of government price negotiation in 2026. Even during the current Medicare bidding cycle for 2024, many brands that do not anticipate being selected for government price negotiation will likely seek to establish a strong position to secure preferred formulary access, enabling them to compete against brands expected to undergo government negotiation in the near-term.

In our next whitepaper, we will unpack the competitive dynamics for scenario 2, a market in which there are two DNP brands, looking at how simultaneous and staggered eligibility for government negotiation for multiple products within a therapeutic area could introduce additional dynamics beyond those discussed in our first scenario. Additionally, we will consider how variables such as WAC price and the level of discounting present in the market today may impact stakeholder incentives and competition post-IRA implementation.

Sources

[1] Although the Inflation Reduction Act refers to the program as a negotiation, HCG assumes that manufacturers will effectively be required to accept the government’s terms, given the penalty for non-compliance is so severe.

[2] For Drug 1, 75% of non-FAMP is assumed to be less than the current Medicare net price.

[3] “A Comparison of Brand-Name Drug Prices Among Selected Federal Programs,” Congressional Budget Office (Feb 2021)

[4] Klein, M., D’Anna, S., Klasner, J., Pierce, K., (31 Aug 2022). The Inflation Reduction Act: What’s Changing in Healthcare?

[5] HCG made this assumption for the sake of simplicity, recognizing that manufacturers may make different decisions after re-evaluating their post-IRA liabilities.

[6] Assumes manufacturers provide 15% rebates; Assumes a patient starts therapy at the beginning of the calendar year, and remains adherent to therapy; Assumes the patient has no other drug spend; For current design, assumes patient enters Initial Coverage Phase after Patient OOP exceeds $480; For current design, assumes patient enters Coverage Gap Phase after Patient TROOP exceeds $1468; For current design, assumes patient enters Catastrophic Coverage Phase after patient TROOP exceeds $7050; DIR fees in Catastrophic Coverage Phase are not accounted for in this model

[7] In special circumstances, plans may wish to prefer a non-DNP brand. Although DNP brands must be covered on Medicare Part D formularies, they are not guaranteed favorable access and plans may disincentivize their use through prior authorization, step edits, and higher cost sharing.